3DO at CES 1995: The Console That Thought It Was Winning

In early 1995 the 3DO stood on the CES show floor filled with confidence, bold claims and a belief that multimedia hardware would shape the future. With hindsight the moment feels both ambitious and misguided, offering a fascinating snapshot of how the industry imagined tomorrow.

If you ever want to understand the psychology of hype, you do not need a textbook. You just need to stand on the CES show floor in early 1995 in your imagination and picture the 3DO Company smiling like it had already won the next decade.

There is something incredibly human about the way people speak when they think the universe is about to reward their optimism. In the months leading up to that show, executives were casually predicting that multimedia hardware was going to reshape entertainment. Commentators were calling 1995 the moment when the so-called 32-bit generation would separate the visionaries from the pretenders. Analysts kept insisting that the “early signs look extremely good”, as if the future had sent a memo confirming its arrival date.

This was the atmosphere that surrounded the 3DO. A mixture of excitement, certainty and a slight inability to imagine that anything could go wrong.

The 3DO Dream

The 3DO was never sold as a simple console. It presented itself as something closer to a civilisation upgrade. It was designed to be the centre of the living room, a bridge between games, films, education, music and interactive storytelling. It carried the belief that a CD-based multimedia machine could replace everything from the family VCR to the home computer.

Developers were encouraged to think bigger, not in polygons but in filmed actors, pre-rendered sequences and ambitious hybrid experiences. The pitch was that once the world embraced full-motion video and high-capacity discs, traditional cartridges would look like fossils.

For a while the industry seemed to agree. Companies talked earnestly about interactive cinema. Large publishers poured money into digitised actors. Studio heads said things like “multimedia is the future of entertainment” with complete sincerity.

People were not pretending. They genuinely believed it.

CES 1995: The Stage Where Everything Looked Possible

CES that year had the vibe of a festival for technological optimism. It was loud, chaotic and full of ideas that sounded brilliant in the moment. Virtual reality displays promised experiences that would change ride design forever. Hardware booths lit entire halls with signage that tried to look futuristic. Studios representing every corner of the industry arrived with prototypes that seemed to prove their particular version of the future.

Amid this spectacle, the 3DO platform looked surprisingly at home. Crowds gathered around its demos. Publishers talked about upcoming titles with the kind of enthusiasm that only appears when a company has not yet looked at its sales charts. Several developers claimed that the system would finally prove what CD-based hardware could really do. One even described the platform as having a “reputation that speaks for itself”, despite the fact that most consumers had not actually seen one in a shop.

This is the intoxicating effect of CES. If you measure the world by the volume of noise in a convention centre, almost anything can look dominant.

The Games That Were Supposed to Carry the Banner

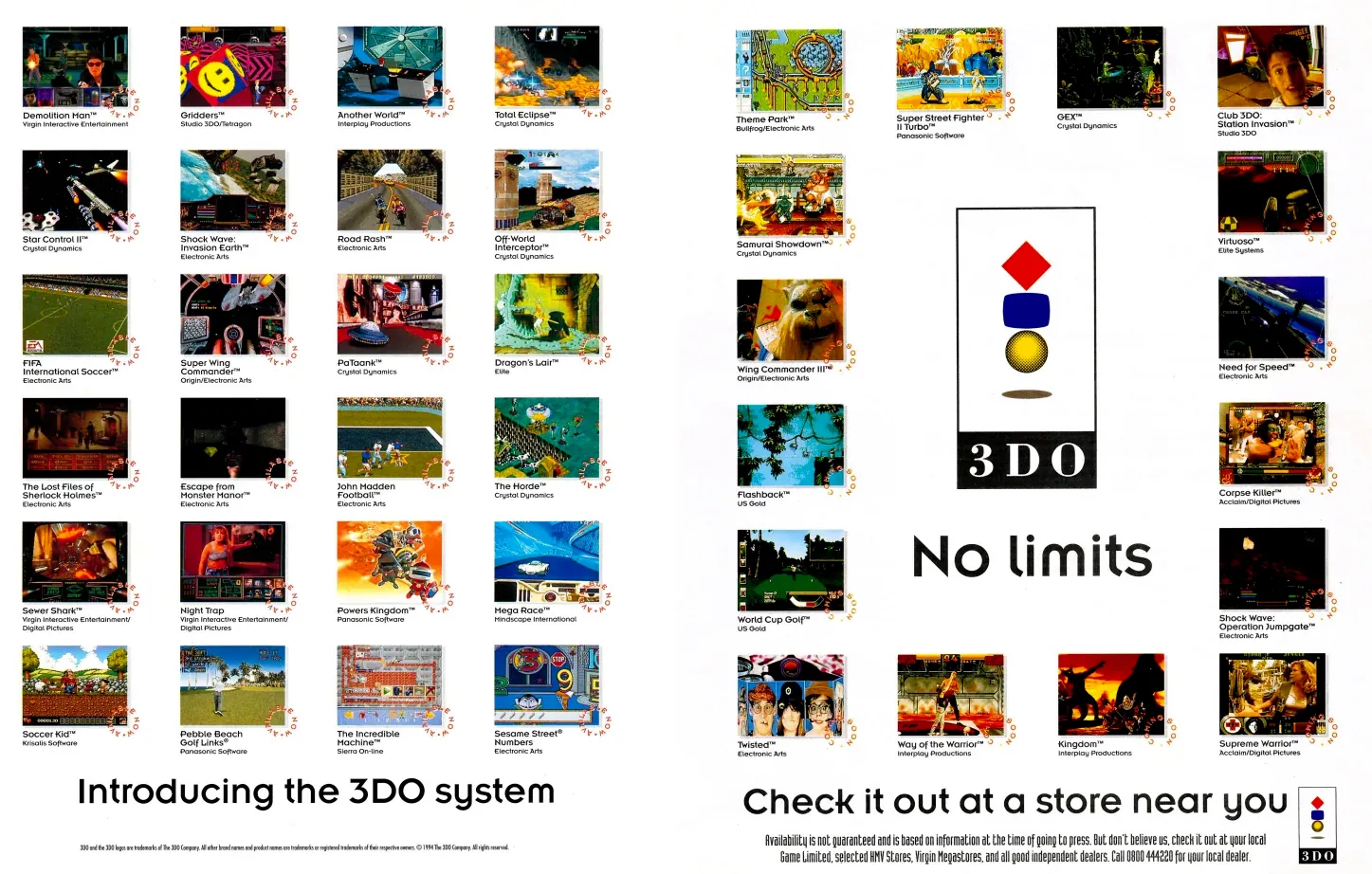

Plenty of games on display reinforced the belief that the 3DO was ready to lead the industry. Some were genuinely promising. Killing Time, which eventually released in 1995, earned a modest cult following for its eerie atmosphere even if critics said its controls were clumsy. Wing Commander III, already a marquee title on PC, arrived on the 3DO the same year and was widely praised for its ambition, though reviewers admitted the system struggled to keep up with its scale.

PC strategy ports added a layer of legitimacy. The Perfect General, which finally reached the 3DO in March 1996, received mixed reviews. Some players appreciated seeing a proper war game on a console, while others felt the presentation had already fallen behind newer rivals. Panzer General, released in 1995, fared better, with critics calling it one of the rare 3DO titles that matched its PC counterpart in depth and enjoyment.

Then there were the hybrids. The Daedalus Encounter, released in 1995 with Tia Carrere in the starring role, was praised for its production values but faulted for being more film than game. Crystal Dynamics’ Off-World Interceptor, which shipped in early 1995, offered chaotic action but struggled to win critics over, largely due to choppy FMV and odd design choices. Even the smaller curios, such as VR-inspired demos and arcade conversions shown at CES, represented a platform throwing ideas everywhere in the hope that at least a few would stick.

The common thread was ambition. Almost every major project leaned heavily on filmed sequences, elaborate pre-rendered backdrops or digitised performances. More video was treated as more sophistication, and there was a genuine belief that cinematic presentation would naturally overtake traditional graphics.

Nobody could see that polygons, not cameras, were about to take over.

Looking back at these titles now feels strangely poignant. Many reached the market. Some were delayed. A few faded instantly into obscurity. And while several earned pockets of appreciation, none shaped the industry in the way their creators expected. The real technological shift arrived from somewhere else entirely, carried by hardware designed around true 3D rendering rather than multimedia spectacle.

The Market That Refused to Play Along

The 3DO had confidence, but confidence is not the same as momentum. While it impressed people at shows, the market outside those halls behaved very differently. The price remained painfully high. Retailers were cautious. Consumers who were willing to spend several hundred pounds on a new machine were already eyeing hardware from companies with stronger track records.

Sony launched its console with a level of strategic clarity that made the industry sit up straight. Sega, despite its own internal problems, still had a loyal audience. Nintendo had not yet revealed its hand, but everyone knew the company would not stay quiet for long.

The 3DO was ambitious, but ambition did not solve the maths. It simply cost too much for too little return. Even as people talked about set-top boxes and multimedia convergence, the system struggled to justify its existence to the average customer.

Within a year, its position in the market became unsustainable. Within eighteen months, the dream was over.

The Gift of Hindsight

There is a line that appears often in period interviews from that time. Someone confidently declares that “this is the biggest year yet”. It never sounds arrogant, just hopeful, like someone trying to convince themselves that the momentum they feel at an industry event will translate directly into real-world success.

Hindsight is a generous teacher. It shows us how sincere people were, how excited they felt, how strongly they believed that their era of technology would usher in something dramatic. It also shows us why they were wrong.

The future did not arrive as FMV.

It did not arrive as interactive cinema.

It did not arrive through a hyper-expensive multimedia box.

It arrived through affordable 3D hardware running fast, inventive games on a platform that understood what consumers actually wanted.

Yet the 3DO’s moment at CES 1995 still matters. It represents a fascinating intersection of optimism and miscalculation, a glimpse into a version of the future that never came to be. It captures an era when the industry was dreaming loudly, even if it was dreaming in the wrong direction.

A Legacy Built on Ambition

What survives today is not the success of the machine, but the energy of its ambition. People remember the 3DO not because it won, but because it tried to become something far larger than a typical console. It aspired to be the future of media at a time when nobody yet knew what that future would look like.

It never got there, but for one strange, glittering moment under the lights of CES, it truly believed it might.

And that belief is what makes the story worth retelling.